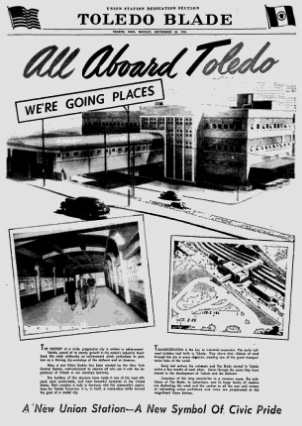

The opening of Toledo’s new Union Station, Central Union Terminal, in September 1950 was a big, big deal to Toledo. After all, who devotes an entire week to celebrating the opening of a train station? 1950 Toledo, that’s who.

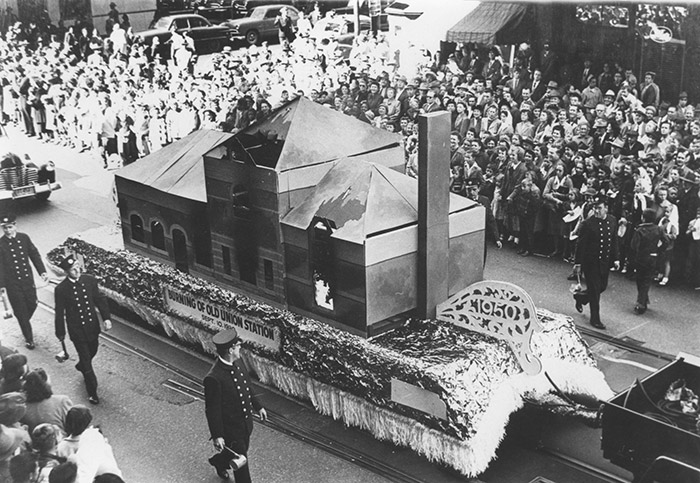

In this post about Toledo’s old Union Station, I recounted the feelings Toledo held towards its old Union Station, a mix of shame, despair and desperation (at being unable to get a new one). It was decrepit, and even a 1930 fire failed to bring about a new station, the New York Central railroad choosing to rebuild instead. World War II held up the progress even further, and it was not until 1945, on the day after the closing of the Toledo Tomorrow exhibit, that the NYC informed the city of its plans to build a new station.

Feelings ran deep. “The inferiority complex which the antiquated station gave this city manifested itself insidiously in various forms. It created the impression that the citizens of Toledo must be awfully stodgy people and generally set in their ways. It contributed to the feeling that Toledo lacked the initiative and the vision to put big civic projects over like other cities,” the Blade wrote in an editorial.

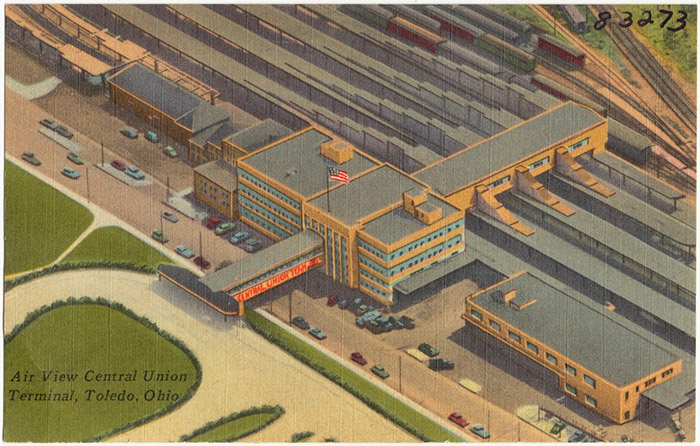

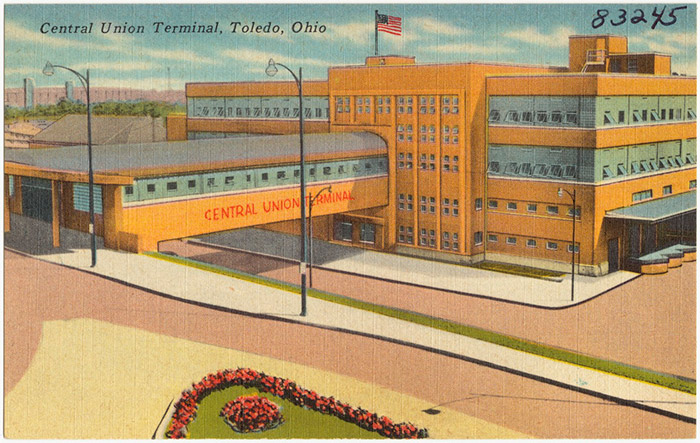

The new station cost $5.6 million and took three years to build, and NYC officials were on hand for the groundbreaking (or spike pulling, as they called it) on October 2, 1947. The latest features and most modern amenities were promised, as well as the use of lots of glass, befitting Toledo’s nickname as the Glass Capital of the World. The station would serve the NYC, the Baltimore & Ohio, the Chesapeake & Ohio, and the Wabash railroads.

At the start of the week, The Blade ran a 28-page section commemorating the event, and reading it is like browsing a history of transportation in Toledo as well as looking at a glossary of Toledo businesses: ones you’ve heard of, like Owens-Illinois, Columbia Gas, Toledo Edison, Libbey-Owens-Ford, Willys-Overland, DeVilbiss, Auto-Lite, Champion, Toledo Scale and some you haven’t, like the Wine Railway Appliance Co.

Advertising proceeds from the section went to fund the activities of Union Station Dedication Week, as it was called, and Paul Block Jr., co-Publisher of The Blade, was the general chairman of the dedication committee, which explains why The Blade ran stories calling the week “the biggest civic celebration in the history of Toledo.”

So The Blade was all over this.

The festivities started on Sunday September 17th, with the closing of the old station and the first train at the new station (a college student bought the first ticket; he was headed to Cleveland). There were juggling, acrobatic and dog acts, concerts and an open house. The entertainment and open house activities continued all week.

70,000 people came out to see the new station on its first day.

Once the new station opened, the old Union Station was quickly demolished.

On Monday the 18th, a new billboard based on the one put up by Kenton Keilholtz (“Don’t Judge Toledo by its Union Station”) was unveiled: “Now! Judge Toledo by its Union Station.” Keilholtz, who had moved to California, came into town to attend the unveiling.

Tuesday the 19th was Young Toledo Day. Schools closed at 2 p.m. and kids crowded the new terminal.

Wednesday the 20th, Ted Mack (of Amateur Hour fame) arrived, and an afternoon tea hosted by the wives of city council members was held.

Thursday the 21st was “Glass Day,” which involved the unveiling of a sand-blasted glass mural inside the terminal.

Friday the 22nd was Dedication Day, which was marked by the arrival of the longest coal train in the world. The 206-car train was more than symbolic, because along with the new station, the NYC had made a large investment in the loading docks at Presque Isle. It was all part of a $15 million investment the NYC had made in Toledo-area facilities (it had 4,000 employees on the payroll in the Toledo area).

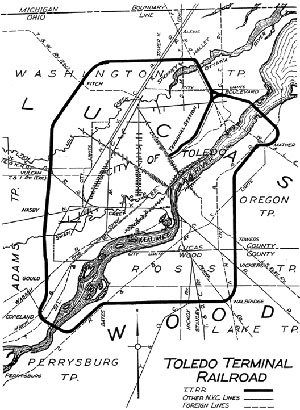

All week long, people enjoyed rides on the Toledo Terminal Railroad on its 29-mile circular route around Toledo. On the first day alone, 1,800 people took the trip. (The old TTRR was active deep into my childhood; the tracks paralleled Douglas Road near where I grew up and crossed Bancroft St., Kenwood Blvd., Central Ave., Sylvania Ave., etc.)

And on Saturday the 23rd, to wrap it all up, there was a gigantic parade through downtown: 31 bands, floats galore, 2-1/2 hours, two miles long. Somewhere between 150,000 to 200,000 people lined the route from 20th and Jefferson, down Summit to Broadway and to the station.

But passenger rail began to fade at almost the same time the stationed opened. The Interstate Highway System would be built, making intercity travel easy. Air travel became safer and faster. By 1967, the NYC’s flagship train, the 20th Century Limited, passed through Toledo for the last time. For a time in the 1970s no passenger trains served Toledo. Today in 2017 it is only four, all Amtrak: the Lake Shore Limited and the Capitol Limited, both twice daily.

The station was one of the last union stations constructed in the United States, according to the Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority, who acquired the station in 1994 and spent $11 million to renovate it. It was renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Plaza in 2001.

Again, from the same editorial:

In celebrating the completion of their Union Station, therefore, the people of Toledo are aware that such an event means much more to them than it could possibly mean to people anywhere else. Just as the old station was the symbol of what they didn’t want Toledo to be, so is the new station the symbol of what can be done to dress up, to improve, to build the greater Toledo they all want.

central union terminal was my “home depot” from 1975 (when i was attending the university

of michigan and amtrak service returned to the facility) through 1980 when, after working

for two and a half years for a toledo broadcasting concern, i moved to manhattan. during those

years, a significant part of my yearly travel involved the terminal. i made between three and six

round trips per year to new york — my original home town. during the same period, i regularly

traveled to chicago and boston using the single train (the lake shore limited) which called at the

facility.

what is interesting in retrospect about the time was the depot was only 25 years old when i became

a regular user. it was fully intact: ticket windows, bathrooms, 1950 otis self-service elevators,

ramps and stairs down to the platforms — even the original lighting fixtures were in place. the steam

heat keep the building toasty and inviting in the winter and somehow, using all those louvered

windows, the penn central and later conrail employees who ran the place kept the un-air conditioned

building quite cool and comfortable in the summer.

the ticket agents who worked there were superb. they were fast and familiar not only with the whole

amtrak system but with the bulky new reservations computer. i could stroll over during lunch

— no internet in those days!! — and quickly purchase tickets or make a reservation to be picked up

later. a lady even reopened the snack bar — so i could have lunch if i wanted.

i guess what i am trying to convey is: even though central union terminal was a time-capsule even then, and even though it was much too big for the single train it served, it still functioned beautifully.

passengers were easily loaded. they were able to do minor repairs if needed. everything was maintained: fresh paint, working lights, modern chairs, a very good public address system which i remember to be — like everything else — straight out of 1950. and the employees worked hard to

help everyone who used the lake shore (which was, itself, a very pleasant ride in those days —

with nice dining cars and really superb crews).

i looked forward to my visits to central union terminal and remember many happy times there!

My Great-Grandfather Henry William Bohm was the New York Central stationmaster when Central Union Terminal open end.