Throughout the 1920s, Toledo made constant efforts to better itself as its population grew. Along with a new Union Station and an airport, better roadways were also at the top of most lists. The News-Bee, in its editorial stances, unabashedly pushed for all these – including the use of the old Miami and Erie Canal as the path for a potential highway.

The canal, which took 20 years to build and was completed in 1845, had long outlived its usefulness. Railroads pushed it into the background ages ago, and low bridges built over it had made most of Toledo’s section of the canal not navigable. There were better uses for the land, such as a wide boulevard out to Maumee, part of a “superhighway” from Toledo to Cincinnati – today’s Anthony Wayne Trail, or simply “The Trail.”

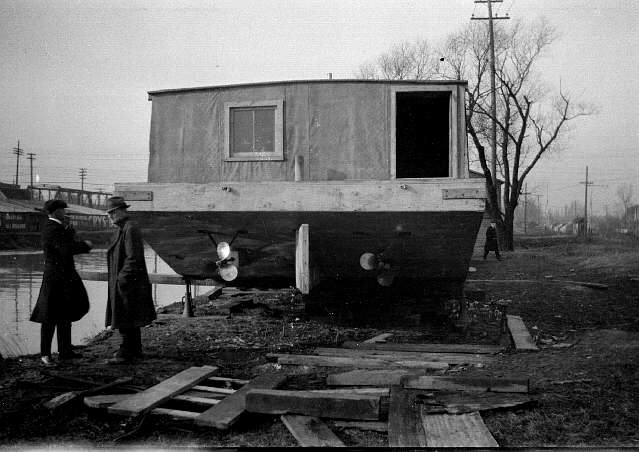

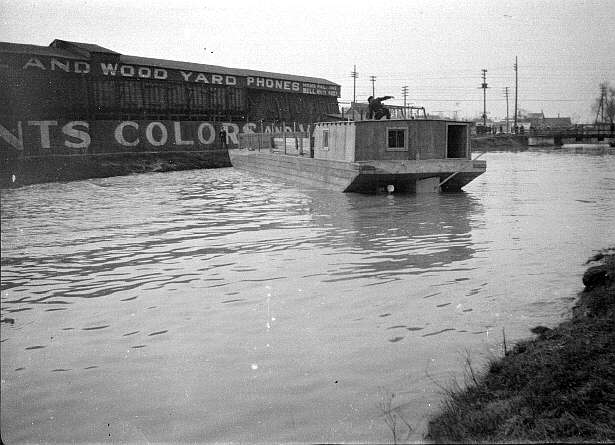

It was 1922 when the last boat to use the canal was launched in Toledo, and there were pictures.

The State of Ohio had to legally abandon the canal right-of-way to do anything with it, and some businesses which still depended on the water flowing through the canal objected – so much so that lawsuits attempting to stop the abandonment were filed. One, Kirk v. Maumee Valley Electric Co., 279 U.S. 797 (1929), made it all the way to the Supreme Court.

In early June 1929, the city got the news that it wanted from the Supreme Court that the stretch of the canal from Toledo to Maumee could be abandoned. I am not a lawyer, but my interpretation was that a power company along the canal had claimed that various leases and agreements over the use of canal water would be broken. The Supreme Court said the main issues were if the state had a duty to maintain the canal, which, it ruled, it did not, and if the state could abandon the canal, which, it ruled, it could. And The News-Bee was overjoyed.

“The decision carries with it civic possibilities which stagger the imagination,” The News-Bee, never one to hold back on civic pride, said in a front page editorial. “It heralds an era of community progress, prosperity and expansion, destined to lift Toledo to commanding heights of achievement.” It also was an opening for “the development, on an extensive scale, of all that territory in South Toledo which has been retarded and stagnated thru the presence of the canal.”

The News-Bee also felt the prospect of a new Union Station was just around the next bend, but alas it was still 21 years off.

With the legal issues cleared up, and commanding heights of achievement awaiting (I apologize, but I cannot read The News-Bee with a straight face sometimes thanks to their blustery prose), state and city officials planned a big ceremony to commemorate the draining of the canal. An auto parade leaving from Colburn and Broadway would include “a large number of prominent pioneer Toledoans,” the News-Bee said. “Many of these will be men and women who recall the days when the canal banks were the scenes of the city’s greatest commercial activity.” Let the draining commence!

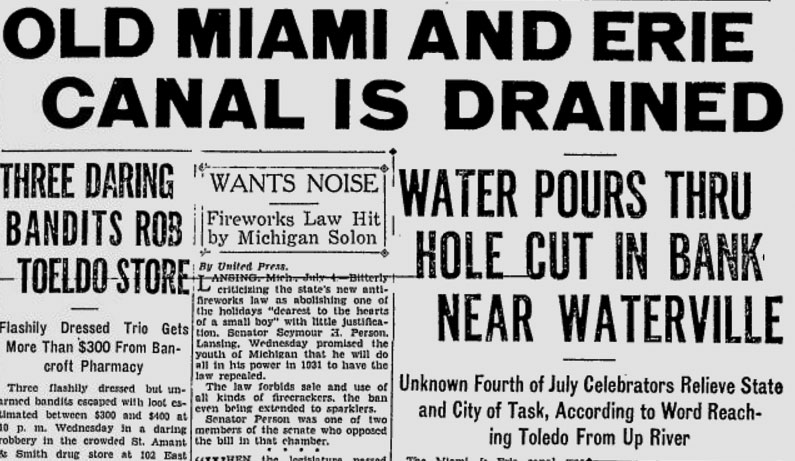

But someone came along on July 3, 1929 to burst the city’s civic bubble.

Persons unknown had cut a large hole into the canal bank three miles below (downstream from) Waterville. The hole might have been cut, or blown open, witnesses said, but at any rate, the canal was draining.

Thus, thru the mysterious hand of some unknown person, the goal toward which Toledo and northwestern Ohio has struggled for many years was being realized, but without the official sanction of any official of Toledo or of the state.

Word that the canal had been cut spread rapidly thru the section bisected by the canal, and persons living along the river bank came to the spot, gazing in wonder at the gap thru which the canal waters are pouring.

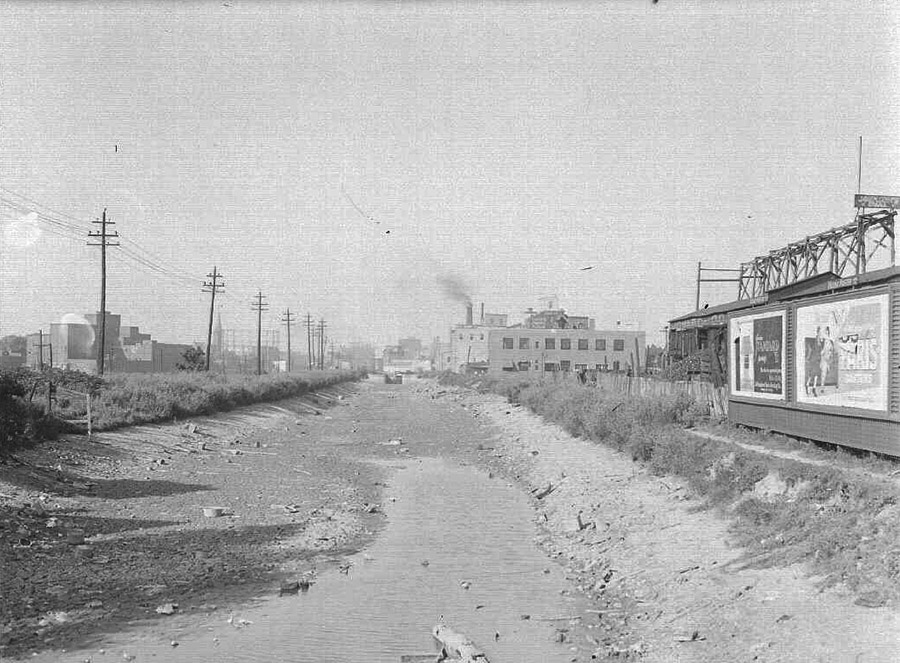

The state started an investigation of who drained the canal, but really it was a moot point. The canal had been drained, leaving behind, well, only a century’s worth of stuff thrown into the canal:

Hundreds of persons walked along the banks, viewing the accumulations of 100 years that had been suddenly revealed.

In some places, where fish had collected in pools, the boys and men waded about making catches with their hands.

At the locks on City Park avenue there was barely a trickle of water passing through.

Nevertheless, officials went ahead with plans – rain or shine, drained canal or not – for a ceremony that involved closing and sealing the gates at the inlet near the Providence mill dam at Grand Rapids.

A crowd of several hundred gathered at the ceremony, which included state and city officials and “a salvo of aerial bombs.” Mayor William T. Jackson recalled “the persistent efforts of individuals and power interests to obtain abnormal repayments for their water-lease rights and he praised Law Director George W. Ritter for the painstaking care he had shown in conducting the legal phases of the case.”

When this post started out, it was going to be about how the Trail was built – when it was built, when it opened, how it got its name, and so forth. But research has turned up very little regarding how it got built.

In the mid-1930s, the Works Progress Administration constructed the Anthony Wayne Trail on the route of the abandoned Miami and Erie Canal. Many of the rocks and boulders torn away from the old canal later were used to construct some of the buildings at the Toledo Zoo.

I did turn up some neat pictures of the new highway however.

Great article! In the 1925 photo showing the dry canal bed, it’s possible this is from 1925. According to some old maps the portion of the canal that ran through Downtown Toledo was abandoned long before the decision to build the Anthony Wayne Trail. So if this is a view looking north into downtown, this portion may have already been abandoned for over 50 years.